Covid-19 and democracy. Let’s start a discussion

What we have been experiencing for many days now is undoubtedly the greatest form of mass freedom restriction that our country has witnessed in its republican history. Restriction imposed by the Government, without having been passed through parliament.

Yet who among us today can deny the need for this limitation to their freedom of movement and self-determination in their choices?

Probably no one. Certainly not the undersigned who, since the March 11 decree of the Conte Government, has always behaved in a manner consistent with the provisions, leaving home as little as possible, and usually only for matters of necessity, except for a few short walks very close to home.

Our organisation then, in advance of the government decree, had already closed its Rome office on 5 March, asking its staff to work from home to avoid travel and possible contagion.

So, in some way, there has been general awareness that some limits have to be set for one’s own good and that of others.

However, it is certainly right – and healthy for our democracy – to question the length and extent of these forms of limitations, the control systems and sanctions created ad hoc to prevent and punish violations and, above all, at what point the limitation measures go too far.

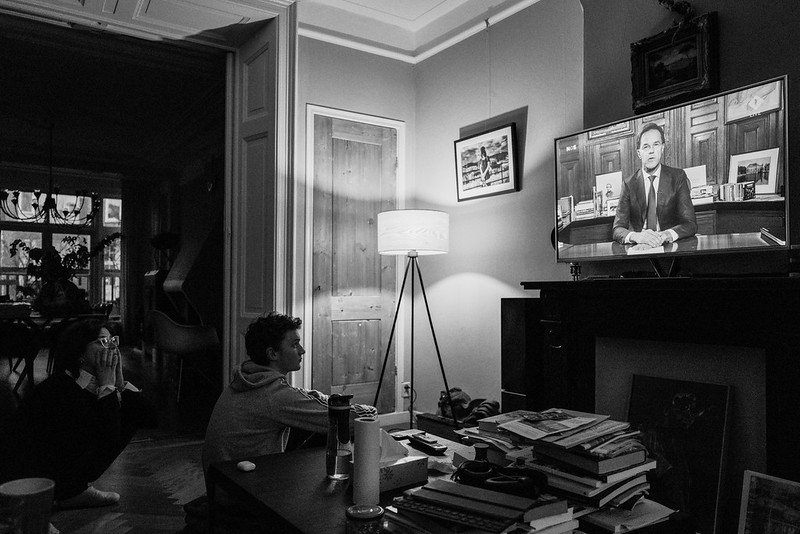

The urban geography of our cities has changed in recent days. The streets are almost deserted. Few cars pass by each other and even fewer people meet.

However, it seemed that even these few were too many and their behaviour appeared incorrect. So further restrictions have arisen, this time mostly passed by mayors who, with special ordinances, have decided to close gardens, parks, dog areas and access to beaches. The Government itself had explained how, without responsible behaviour on the part of citizens, the restrictive measures would be extended, alike the further restrictions placed on outdoor sports and even more restrictive hours for supermarkets (launched in this case by individual regions).

The Minister of the Interior, Mrs. Lamorgese, specified that if it were necessary, it would be possible to mobilise the army to enforce the prohibitions, which, moreover, happened in Campania by decision of the National Committee for Order and Security.

In the meantime we know that, as of 23 March, 2,244,868 individuals have been stopped for regular controls and 104,664 people have been fined. Huge numbers, if you consider how few people have been on the streets recently. Some municipalities, like the one in Rome on the weekend, have ordered their local police to create checkpoints where all the cars can be stopped and not just a few at random. In addition, a new government decree, approved just yesterday, has provided for a further increase to fines – now up to 4,000 euros for those who do not respect the bans on movement and the rules of containment – and gives the presidents of the region the power to issue more restrictive orders.

In the meantime, Lombardy has used a system to analyse the movements of the population through data collected and provided by telephone companies; an initiative that others have declared they want to follow. This is a form of control which for the moment is not personal (from what we understand, data is collected in aggregate and anonymous form), but certainly there is a risk that we could instead move to using this data to monitor and punish individual behaviour, as done by some countries. This is not something we should underestimate and deserves reflection.

Romania, Moldova, Latvia and Armenia, four member countries of the Council of Europe, then activated an article of the European Convention on Human Rights that allows them to derogate its application. This is a worrying step that may suggest how the need to combat Covid-19 can lead to wide exceptions in the field of protection of human rights. In Italy this intention, at the moment, does not seem to be there, but it is still probably useful to reflect on this today, not only in view of the battle against Covid-19 still ahead, but also in consideration of the state in which we will find our democracy in the post-coronavirus period.

So what is the limit, if any, beyond which one should not go in the restriction of freedom? To what point should it be possible to sacrifice forms of individual freedom and increase control over people? To what extent can the containment of the virus, and the right to health (individual and public) justify the subordination of any other right (individual and public)? And how long can these controls last for, seeing as there seems to be agreement between scientists and doctors that the coronavirus emergency will last for several more months, and the Government seems ready to extend the current measures beyond their originally identified expiry date? Yesterday’s decree indicates that until July 31 there may be the possibility of extending them from month to month depending on the progress of the contagion.

In the coming days we will continue to address the difficult issue of the coronavirus emergency, and its impact on democracy and rights, through a series of in-depth studies.

Cover via Flickr