Pro Bono for Social Change – How To

What is pro bono and why does it matter? Furthermore, what can pro bono offer you and what is the best way to deliver and receive it?

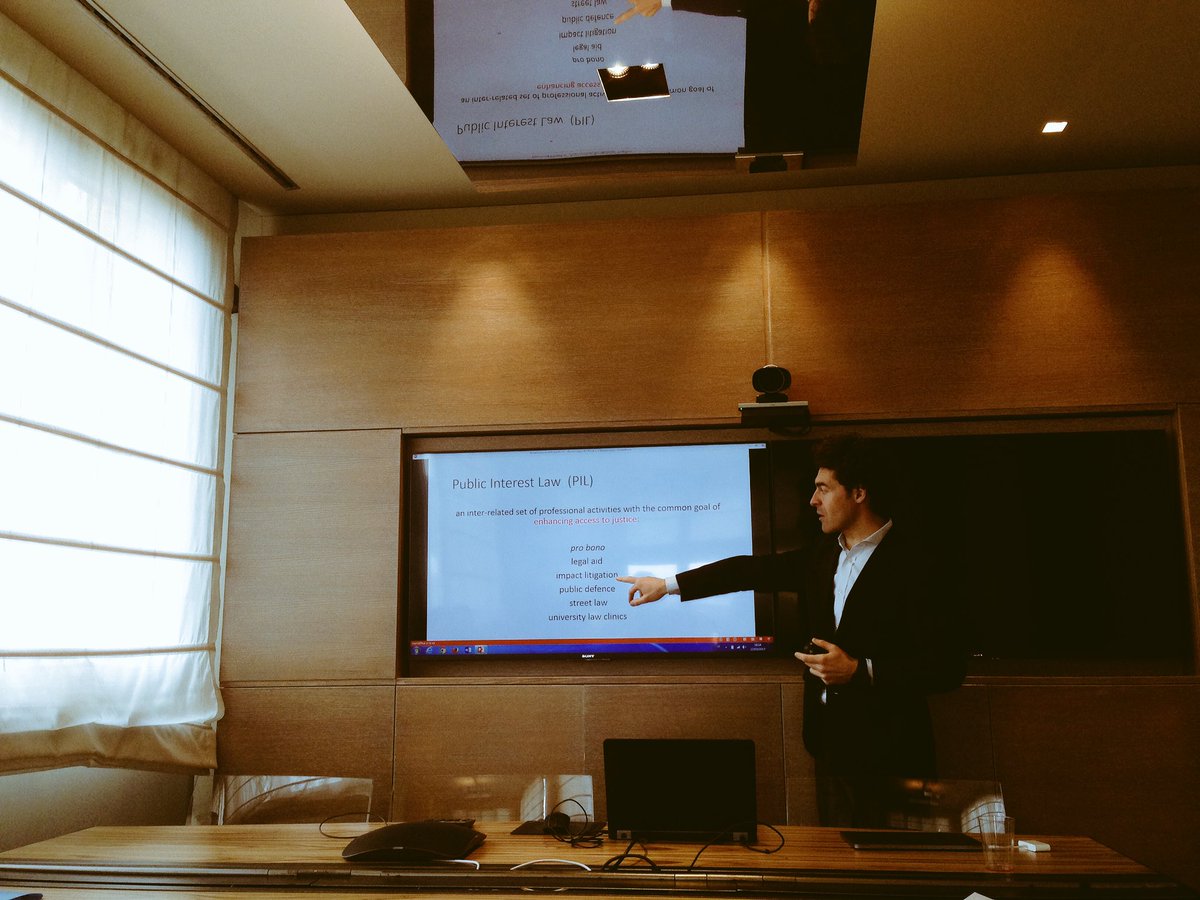

These are the fundamental questions we were asked to reflect upon during the very first Pro Bono Masterclass, which was held in Rome by The Good Lobby (with the gracious support of the Italian Pro Bono Roundtable & Pilnet and the hospitality of Orrick Italy). The masterclass was given by Alberto Alemanno – professor at HEC Paris & the NYU School of Law as well as co-founder of The Good Lobby and author of “Lobbying for Change” – and aimed at teaching the fundamentals of pro bono for social change to NGO staffers and activists who need legal support as well as to lawyers willing to provide it.

Why we (badly) needed a Pro Bono 101

In short, Alberto led us through a fast-paced and fully-packed “Pro Bono 101” with the aim of enabling all participants to acquire a holistic idea of what pro bono actually is and how to fully reap its potential.

This is sorely needed as Italy and other civil law countries have long been lagging behind as far as the development of a “pro bono culture” is concerned, something which, on the contrary, is deeply-rooted in the Anglo-Saxon system. Mind you, this is actually somewhat paradoxical, as we were the ones who invented pro bono! In fact, public interest law and pro bono are concepts which date back to the Greek and Roman empires and which were developed over centuries of rich history. Be that as it may, in Anglo-Saxon countries all major law firms have stringent pro bono obligations; that is, all lawyers have to use some of their working hours (the average is around 20 hours a year) for pro bono legal assistance.

Things, however, are quite different in Italy and other countries where there is not only a persistent lack of pro bono culture, but sometimes even active resistance from bar associations, which often perceive pro bono work as competing with the regular demands of providing legal aid (i.e., assistance to people otherwise unable to afford legal representation and access to the court system through the support of the State, which pays the lawyer’s fee on their behalf). In other words, there still much to be done to spread awareness about the huge potential of pro bono in driving social change in Italy and Europe.

For this reason, the work being carried out by Pilnet – the global network for public interest law – to create a strong European Pro Bono circuit is of the utmost importance and we here at Cild are extremely proud to be a part of that process through our participation in the Italian Pro Bono Roundtable (in which is now coming into being “Pro Bono Italia”, an independent association made up of law firms and lawyers willing to promote the pro bono culture in Italy) and the further development of our own Clearing House, which aims to connect legal advice providers – that is, law-firms and lawyers – to NGOs and other civil society entities. Our Clearing House is about to celebrate its second birthday but there is still a lot to be done to ensure that it is working at its full potential, and this is mostly connected to the lack of awareness – on both sides (in other words, both lawyers and civil society members) – as to what pro bono is and how to make use of it.

What is pro bono and why is it so important?

Public interest law is an interrelated set of professional activities – ranging from pro bono and legal aid to impact litigation, public defence, “street law”, and university law clinics – with the common aim of enhancing access to justice.

(Legal) pro bono is professional legal work undertaken voluntarily and without payment. Unlike traditional volunteerism, it is aid that uses the specific skills of legal professionals to provide services to those who are unable to afford them.

Pro bono has huge and complex transformative potential.

First and foremost, it offers an invaluable opportunity for civil society associations and NGOs, which are not “only” provided with free legal assistance they would not otherwise be able to seek and thus facilitated in continuing their social mission, but they are also empowered in a broader way: they are able to go beyond litigation and maximize their advocacy opportunities and impact; in addition, they are able to gain a seat at the bargaining table through the opening of participatory channels and thereby able to do evidence-based policy making by speaking the language of the decision makers. This can (and should) result in stronger action by civil society actors and thus facilitate the progression of social change in an extremely concrete way.

Furthermore, pro bono has huge potential with regard to law firms and lawyers. To begin with, there is the obvious aspect of moral and ethical commitment: motivated lawyers are happy to be able to do something good for their community. Indeed, many lawyers engaged in pro bono stress the happiness, personal satisfaction, and growth that comes of their free services. Then there is also the opportunity for professional development: the legal experience junior lawyers acquire while working pro bono cases offers them the opportunity to try cases they might otherwise wait years to get; for senior lawyers, doing pro bono can be a refreshing and stimulating way to fight career fatigue and acquire new professional perspectives.

Finally, there is also an obvious networking and reputational component: pro bono work opens up new and important relationships for law firms and shows them to be positive actors in the drive towards greater social justice.

To sum up: there are numerous good reasons – for all concerned – to join in!

How does it work?

The building of a pro bono network is just like a puzzle: you just need to put all the pieces in the right place to get a new picture. On the one hand, there are the law firms (which usually have dedicated staff and structures but can also adopt different working methods through externships and rotations) and on the other, there is civil society. In between the two are the clearinghouses whose job it is to facilitate the relationship between legal advice providers and those who need it.

This may seem incredibly complex, but it is not as difficult as you may think once you get the basics right – something which Alberto taught us by having us get some hands-on experience through a role play. In this simulation we used a fictional request as example to learn how to set the work on the various aspects and to reflect on the processes of pro bono as well as on interaction between different actors.

Here’s how it works:

- The NGO has some kind of “legal need” (mind you, the definition is rather open-ended: this can range from administrative and fiscal questions – e.g., statutory modifications – to more substantial matters – for example, the carrying out thorough research or the shaping of a litigation strategy) and communicates it to the Clearing House;

- The Clearing House assesses and refines the request, helping the NGO to better shape the terms of the question while also identifying and correcting possible criticalities (and, for more complex matters, constructing a roadmap) and evaluating its potential impact;

- The Clearing House then pitches the request to the Pro Bono network and assigns a willing legal assistance provider who is usually identified on a first-come-first-served basis (but this criterion can obviously be waived when there is need for specific expertise);

- Even once the matchmaking is done, the Clearing House remains a part of the process by monitoring and facilitating the relationship between the NGO and the legal advice provider and conclusively evaluating its output.

For instance, here is the case we tried to tackle:

- Fictional NGO X, which works in the field of migrants and refugees rights, is providing legal assistance to an asylum seeker whose international protection request has been denied by the Territorial Commission. A lawyer who collaborates with NGO X is already following up his appeal before the Tribunal but he needs support in putting together strong documentation demonstrating the partiality of the Country of Origin Information (COI) on which the Territorial Commission based its denial decision. NGO X thus contacts Pro Bono Clearing House Y to ask for help;

- Clearing House Y helps NGO X to specify the content and timing of the request as well as highlight the potential strategic impact of the research and litigation in terms of demonstrating the need to revise the COI used by the Territorial Commissions in Italy (which indeed presents many issues, as argued in a recent study) as well as those used by the competent authorities in other countries;

- NGO X’s request is pitched to the Pro Bono network by Clearing House Y, which highlights its core elements as well as its strategic impact;

- Lawyers and law firms involved in the Pro Bono network assess the request and their ability to work on it successfully (evaluating their competence and capacity but also potential conflicts of interest); those interested contact Clearing House Y to express their interest in taking on the case;

- Clearing House Y assigns the case to lawyer/law firm W; a deadline is given and the Clearing House monitors the collaboration through to its completion;

- NGO X receives thorough legal research from lawyer/law firm W and uses it to fight for the acknowledgement of international protection for the concerned asylum seeker!

Have we succeeded in convincing you to try out the potential of Pro Bono legal assistance?

Contact our Legal Action Centre to find out more & to get involved!