Immigration detention centres in Italy are inhumane, oppressive and costly

Italy’s CPRs are black holes in which serious violations of the fundamental rights of detained migrants continually occur. Migrant detention facilities are managed by private companies which, through taxpayers’ money, make an enormous profit at the expense of detained migrants and basic human rights.

Following the adoption of a new securitarian immigration decree (Decree Law n. 20/2023), launched after a deadly shipwreck in Cutro, the government aims to adopt a second immigration decree which provides for the construction of new detention facilities and an increase of maximum detention time up to 18 months; detention which can be described as detention without charge.

The adoption of new securitarian measures, such as the creation of new detention facilities and the increase in maximum detention time, will neither be useful in managing migration flows nor in increasing repatriations, contrary to what was suggested by Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, who recently spoke on the matter. Instead, such measures are likely to be even more costly than current measures, both from an economic and humanitarian point of view.

From an economic perspective, the management of the CPRs currently running in Italy has cost taxpayers over 50 million euros over the past two years. Running CPRs is a very profitable business for these firms, something CILD denounced in our recent report “L’Affare CPR” (The CPR Affair). CPRs are managed by private companies and multinationals which, despite the low offers, continue to profit from the management of administrative detention to the detriment of detained migrants and their fundamental human rights. The opening of new detention centres will further increase this expenditure, at a historical moment in which inflation is hitting citizens and the costs of all goods, including necessities, continue to rise.

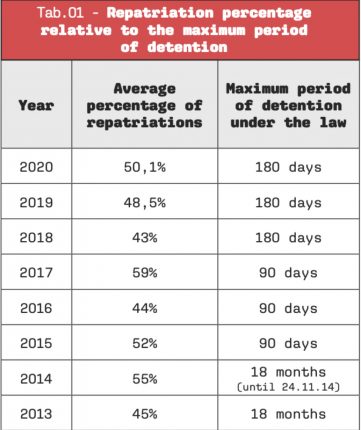

Such an increase in costs is not matched by an increase in the efficiency of CPRs as a tool for managing migration policies. If we look at the issue in terms of the “effectiveness of the system”, according to the data from the latest report of the Guarantor of the Rights of Persons Deprived of Personal Liberty, in 2022 an average of 49.4% of the people detained were repatriated, and in some detention centres the percentages are even lower. For example, in the CPR of Macomer (Sardinia) only 23% were repatriated, and in the CPR of Rome, only 25% were repatriated. Despite the increase in detention time, percentages have remained the same over the past 25 years. Moreover, detention itself is illegitimate, as the Guarantor recalled in their 2021 report to Parliament: “Such deprivation is justified by a feasible hypothesis of repatriation: this makes the restriction of liberty illegitimate when there are no agreements with the country of destination that make this hypothesis concretely achievable”. Similarly, the detention of those who cannot be repatriated due to the highly unstable situation in their countries of origin is unjustified.

From this point of view, the increase in detention time up to 18 months will not change anything, except extending the time over which migrants’ rights are violated. The CPRs have now existed for 25 years – a sufficient period over which to realise that people are either identified or repatriated in the first few weeks, or it will no longer be possible to do so. In the past, detention time was already fixed at 18 months and during the same period, the percentage of repatriations drastically reduced (as reported in our research “Black Holes“), indicating a decline in the “effectiveness” of this measure.

Increasing detention time to a year and a half is concerning noting likely implications on human rights. Although the CPRs have existed for a very long time, they have not been provided with a comprehensive set of laws and rules to regulate internal life and human rights protection – unlike, for example, the criminal detention system. This legal gap has repercussions precisely on migrants’ fundamental rights which are systematically violated by private companies and public institutions that often fail in their supervisory duties. We are therefore witnessing serious violations of the right to health, legal defence, and communication with the outside world. In short, even from this point of view, the CPRs are black holes.

Effective migration management certainly does not involve an increase in detention time. We believe it is increasingly necessary and urgent to opt for alternatives to irregularity that allow the people who are detained to access regularisation. Unlike the stereotyped narrative that is often offered by mainstream media and political propaganda, migrant detention facilities are filled with people who were typically already employed in the country, already have a family in the country, and who find themselves losing their residence permit following the loss of their job. We believe that such a situation can be managed and solved very differently, and more effectively.

As CILD, we believe that it is necessary to overcome the administrative detention system, both because it is useless and, above all, because of the inhumane and degrading treatments that occur every day within the CPRs.