Blowing the whistle on drone strikes

di Philip Di Salvo

US drone warfare has an ongoing accountability and transparency issue. Especially during the Obama years, a timeframe in which the use of drones in countries where no official war has been declared has escalated, the public has been given very little chance to access data and information concerning the scale and effects of the phenomenon. The official data on drone strikes released recently by the White House conflicted with the figures gathered and published by some NGOs over the past few years. Especially when it comes to the number of civilian casualties involved in the strikes, the numbers are at odds.

Earlier in August, the American Civil Liberties Union won a FOIA lawsuit against the Obama administration, which led to the publication of “a redacted version of the White House document that sets out the government’s policy framework for drone strikes,” officially known as the Presidential Policy Guidance. The release of this document brought up more details concerning how drone operations are conducted and managed, but it was also a sign of how the drone-strike puzzle is still missing several pieces.

In this context of a lack of transparency, and with information regarding drone operations being classified and taken away from public scrutiny, citizens and journalists willing to shed light on drone strikes have another resource to rely on: whistleblowers. Over the past several years some individuals formerly involved in drone operations have become whistleblowers and revealed important details about how strikes are conducted. “Whistleblowers provide a unique and invaluable contribution to the global debate surrounding the US drone program,” says Jesselyn Radack, National Security & Human Rights director of WHISPeR (Whistleblower & Source Protection program) at ExposeFacts.

“The U.S. government regularly releases secret information about the programme aimed at promoting it as effective and harmless. Whistleblowers can tell the public from first-hand experience that the drone program is neither harmless nor effective at stopping terrorism.”

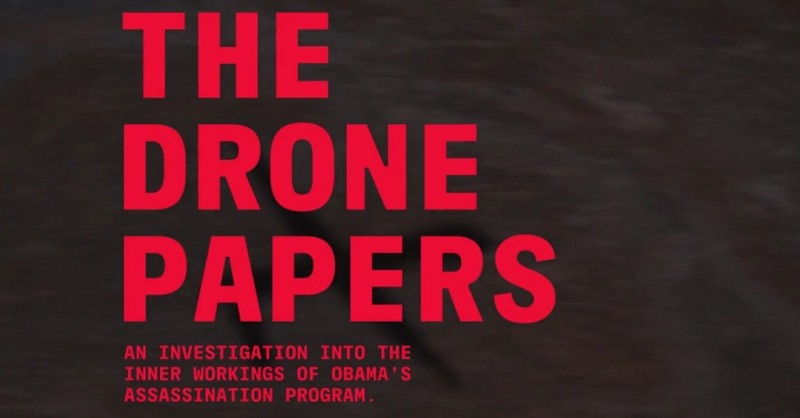

So far the most comprehensive leak coming from within the US Army concerning drones was published in late 2015 by The Intercept under the name of “The Drone Papers”. The whistleblower, quoted as coming from within US intelligence, leaked a significant trove of documents about the US military’s drone assassination program in Afghanistan, Yemen, and Somalia, including details of the chain of command behind it.

Among other elements, “The Drone Papers” brought more information about the involvement of the National Security Agency (NSA)’s Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) operations in drone strikes. In particular, according to the information released, SIGINT is used to “identify and find new targets, the documents detail how military analysts also relied on such intelligence to make sure that they had the correct person in their sights and to estimate the harm to civilians before a strike,” write Cora Currier and Peter Maass on The Intercept.

The NSA’s involvement with the targeted killing programme was also part of Edward Snowden’s 2013 leak. Some documents published by The Washington Post in 2013 exposed how the NSA was cooperating in the program. In 2014 an unnamed drone operator blew the whistle to The Intercept confirming how “rather than confirming a target’s identity with operatives or informants on the ground, the CIA or the US military then orders a strike based on the activity and location of the mobile phone a person is believed to be using.”

According to Jesselyn Radack, looking at the whole picture, “Whistleblowers have revealed that, despite the claims of US national security officials, drone strikes are not always precise, that they create more terrorists than they kill, and that American service members in the drone program are not unaffected by their work, resulting in a destructive culture of alcohol and drug abuse, high suicide rates and high dropout rates.” The list of drone whistleblowers is getting longer.

Brandon Bryant, Michael Haas, Stephen Lewis and Cian Westmoreland are four former US Air Force drone operators and technicians who came forward to speak with The Guardian in 2015 about details of their involvement with drone strikes in Afghanistan and other conflict zones. The four are also authors of an open letter addressed to President Obama, US Secretary of Defense Ashton B. Carter, and CIA Director John O. Brennan calling the US drone programmes “one of the most devastating driving forces for terrorism and destabilization around the world.” Speaking to The Guardian, Bryant said he knows to have been involved in the killing of 1626 people, a figure included in the report card he was given when honourably discharged in 2011. Haas, according to the Guardian, never looked at his record.

Cian Westmoreland, who served as a communication technician in Afghanistan, also spoke about the psychological consequences of being involved in drone killings and the distress of up to12-hour shifts. A 2013 study by the Department of Defense had also concluded how drone operators firing from a distance suffered the same forms of stress and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder as those on the battlefield.

“Whistleblowing is a symptom of a broken system,” says Jessica Dorsey, Pax for Peace Program Officer and Coordinator of the European Forum on Armed Drones, “because governments are not transparent with information regarding drone usage, the public, whistleblowers have stepped in to help fill the gaps. These people put themselves at great risk in releasing this information to the public.” Bryant and Haas are also among those who speak about drone strikes included in Tonje Hessen Schei’s 2014 Drone documentary, a film which outlined more details concerning the US drone program and its effect on people on the ground, especially in Pakistan. Overall, the amount of information available is still limited and insufficient to provide a full picture of the impact of drone strikes.

“Certainly a number of documents have surfaced in many instances in which whistleblowers were involved, and those documents do shed light into systems where otherwise we wouldn’t have data,” says Jessica Dorsey. “However, whistleblowers should not be what we as civil society rely upon. States have a duty to disclose information such as numbers, policies practice, investigation into number of casualties, names of victims and locations of strikes investigated.”

Lisa Ling is also a former drone system technical sergeant turned whistleblower. Her story, along with the ones of two other two whistleblowers, is part of another documentary, Sonia Kennebeck’s National Bird , which premiered in 2016. Ling and Westmoreland also spoke in July at the European Parliament in Brussels during a hearing on armed drones, providing their knowledge and views on the subject. Drone strikes affect European countries too, although Britain is the only one using armed unmanned aircraft, The Guardian writes. Still, US bases in Europe play a part in how the drone programs are operated. Ramstein in Germany is known to be the most important facility, while the role of Sigonella, in Italy, is still less detailed.

“Much like the US program, these countries are also shrouding their cooperation in secrecy,” says Jessica Dorsey. “A number of whistleblowers cooperating with investigative journalists have uncovered fragmented details outlining the involvement of Germany or Italy, for example, but again the information gathered does not paint a wholesale picture of who is carrying out which strikes, under what legal authority, against whom and where. This secrecy undermines accountability, which deprives the victims of drone strikes of their right to an effective remedy.”

Speaking to The Nation for a major feature article on Ramstein, Lisa Ling expressed her idea on why drone strikes are — falsely — considered effective:

“We are in the United States of America and we are participating in an overseas war, a war overseas, and we have no connection to it other than wires and keyboards. Now, if that doesn’t scare the crap out of you, it does out of me. Because if that’s the only connection, why stop?”

Christopher Aaron, instead, is a former CIA employee who worked in Afghanistan and Iraq within the drone programmes. Speaking at an event at the William S. Boyd School of Law in March, Aaron paid tribute to fellow drone whistleblowers in inspiring him to speak out and added: “I began to see with my own eyes that what I was told was very far from what I was experiencing,” and, going to the essence of whistleblowing, “we have the opportunity to expose this policy of perpetual war by sharing compassion with victims, with perhaps a hint of forgiveness. We have the opportunity to shine some light through this darkness.”

Whistleblowers thus have the chance to bring information to the surface which would not be available to the public otherwise. The crucial point, then, is how free and protected they are to speak publicly without risk of retaliation. In the US, the situation is troubling: “most national security whistleblowers are excluded from protections that cover federal employees. Military whistleblowers have some protections, but they cannot be used as a defense to an Espionage Act prosecution, and the Obama administration has brought more Espionage Act cases against whistleblowers than all past American presidents combined,” says Jesselyn Radack, who has defended several whistleblowers. “Additionally, my clients who have exposed misconduct in the drone program have suffered retaliation such as the US government telling their parents that my clients are on an ISIS kill list and the only way to stay safe is to stop discussing the drone program.”

Among the pieces still missing, to begin with, the public needs “a full disclosure of a comprehensive legal analysis…[and] clear definitions on terms being used would be a good start in assisting civil society and other organizations and entities to analyze whether the government’s actions are lawful or not,” concludes Dorsey.

While a comprehensive and transparent process in drone warfare may still be far to be reached, the service provided by the courage of whistleblowers appears to be more and more necessary. In order to push for change and improvements, whistleblowers Brandon Bryant and Cian Westmoreland have joined forces with other activists and former military workers. Their new organization is called Project Red Hand.

Philip Di Salvo is a researcher and a journalist. His research interests include digital whistleblowing, digital security in journalism and the relationship between hackers and reporters. He is currently working on his PhD dissertation at Università della Svizzera italiana (Lugano, Switzerland), where he also works as editor for The European Journalism Observatory. As a freelancer, Philip mainly writes for Wired Italy and other publications.